More than 10,000 Jews Fought for the Confederacy

By Thomas C. Mandes

Special to the Washington Times

6-18-2

The term "Johnny Reb" evokes an image of a white soldier, Anglo-Saxon and Protestant and from an agrarian background. Many Southern soldiers, however, did not fit this mold. A number of ethnic backgrounds were represented during the conflict.

For example, thousands of black Americans fought as Johnny Rebs. Dr. Lewis Steiner of the U.S. Sanitary Commission observed that while the Confederate army marched through Maryland during the 1862 Sharpsburg (Antietam) campaign, "over 3,000 negroes had arms, rifles, muskets, sabers, bowie knives, dirks, etc. And were manifestly an integral portion of the Southern Confederate Army."

There also were Hispanic Confederates. Col. Santos Benavides, a former Texas Ranger, city attorney and mayor of Laredo, Texas, commanded the 33rd Texas Cavalry, while Gen. Refugio Benavides protected what was known as the Confederacy of the Rio Grande. Recent Irish Catholic immigrants also chose to fight for the South, as did a few stalwart Chinese who served nobly in Louisiana.

The largest ethnic group to serve the Confederacy, however, was made up of first-, second- and third-generation Jewish lads. Old Jewish families, initially Sephardic and later Ashkenazic, had settled in the South generations before the war. Jews had lived in Charleston, S.C., since 1695. By 1800, the largest Jewish community in America lived in Charleston, where the oldest synagogue in America, K.K. Beth Elohim, was founded. By 1861, a third of all the Jews in America lived in Louisiana.

More than 10,000 Jews fought for the Confederacy. As Rabbi Korn of Charleston related, "Nowhere else in America - certainly not in the Antebellum North - had Jews been accorded such an opportunity to be complete equals as in the old South." Gen. Robert E. Lee allowed his Jewish soldiers to observe all holy days, while Gens. Ulysses S. Grant and William T. Sherman issued anti-Jewish orders.

Many young Jews served in the ranks. There were a number of Jewish officers who were part and parcel of Southern society. They had spent their formative years in the South defensive about slavery and hostile about what they perceived as Northern aggression and condescension toward the South. Some of the more notable among the officer corps included Abraham Myers, a West Point graduate and a classmate of Lee's in the class of 1832. Myers served as quartermaster general and, before the war, fought the Indians in Florida. The city of Fort Myers was named after him.

Another Jewish officer, Maj. Adolph Proskauer of Mobile, Ala., was wounded several times. One of his subordinate officers wrote, "I can see him now as he nobly carried himself at Gettysburg, standing coolly and calmly with a cigar in his mouth at the head of the 12th Alabama amid a perfect rain of bullets, shot, and shell. He was the personification of intrepid gallantry and imperturbable courage."

In North Carolina, the six Cohen brothers fought in the 40th Infantry. The first Confederate Jew killed in the war was Albert Lurie Moses of Charlotte, N.C. All-Jewish companies reported to the fray from Macon and Savannah in Georgia. In Louisiana, three Jews reached the rank of colonel: S.M. Hymans, Edwin Kunsheedt and Ira Moses.

Many Southern Jews became world-renowned during this period. Moses Jacob Ezekiel from Richmond fought at New Market with his fellow cadets from the Virginia Military Institute and became a noted sculptor. His mother, Catherine Ezekiel, said she would not tolerate a son who declined to fight for the Confederacy.

He wrote in his memoirs, "We were not fighting for the perpetuation of slavery, but for the principle of States Rights and Free Trade, and in defense of our homes which were being ruthlessly invaded."

In tribute to Ezekiel, it was written, "The eye that saw is closed, the hand that executed is still, the soldier lad who fought so well was knighted and lauded in foreign land, but dying, his last request was that he might rest among his old comrades in Arlington Cemetery."

The most famous Southern Jew of the era was Judah Benjamin. He was the first Jewish U.S. senator and declined a seat on the Supreme Court and an offer to be ambassador to Spain. Educated in law at Yale, he was at one time or another during the war the Confederacy's attorney general, secretary of war and secretary of state. After the war, he settled in England, where he became a lawyer and wrote a seminal legal text.

Simon Baruch, a Prussian immigrant, settled in Camden, S.C. He received his degree from the Medical College of Virginia and entered the conflict as a physician in the 3rd South Carolina Battalion, where he joined the fighting before the Battle of Second Manassas. He eventually became surgeon general of the Confederacy.

While he was away during the war, his fiancée, Isabelle Wolfe, painted his portrait in the family home in South Carolina. It was at this time that Sherman began his March to the Sea. His raiders set the Wolfe house afire, and as she rescued the portrait, a Yankee ripped it with his bayonet and slapped her. Witnessing this, a Union officer gave the attacker a beating with his sword.

From this, a romance began to blossom - quickly squelched by the young woman's father, who remarked: "Marriage to a gentile is bad enough, but marriage to a Yankee, never, ever, it is out of the question." Isabelle Wolfe eventually married Baruch. After the war, they moved to New York City, where he set up what became a prominent medical practice on West 57th Street.

Mrs. Baruch became a member of the United Daughters of the Confederacy, and the couple raised their children with pro-Southern views. If a band struck up "Dixie," Dr. Baruch would jump up and give the Rebel yell, much to the chagrin of the family. A man of usual reserve and dignity, Dr. Baruch nevertheless would let loose with the piercing yell even in the Metropolitan Opera House.

Their son Bernard became the most successful financier of his time and one of the best-known American Jews of the 20th century. Bernard Baruch was an adviser to presidents from World War I to World War II and became a confidant of President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

Today, little remains of the Jewish Confederate South. With the mass migrations from Russia and Eastern Europe, new immigrants knew little if anything of the struggle that had ensued during the preceding half-century. Confederate Southern Jewry eventually disappeared.

Thomas C. Mandes is a physician in Vienna, Va. http://www.washtimes.com/civilwar/20020615-7163682.htm

Israelites in the South

by L. T. McGehee

The South of a half century ago was dominated by small towns. Every county seat had a Jewish merchant or two, in almost all instances esteemed pillars of the community. (Our hometown had the Fagenbaums and the Greenstones, and nearby Union City had the Schatz family.) From early on, large enclaves of Jewish families were leading citizens in Richmond, Charleston, Savannah, Atlanta, Birmingham, Mobile, New Orleans, Nashville, and Memphis.

With Jewish presence and influence in the South dating back to pre-Revolutionary times and throughout the years of westward expansion, it came as a surprise to learn that there were only 20,000—maybe 25,000 at the most—Jewish southerners in the eleven Confederate States at the time of the Civil War.

The Confederate-area population was about twelve million people, a fourth of them African-Americans. So, the Jewish presence in 1860 was about two-tenths of one percent of the South’s population. That being the case, the extent of Jewish participation in the Confederacy was all out of proportion to the number of Jewish people living in the region.

Robert N. Rosen has done impressive research on the role of southern Jews in the Civil War. His book, The Jewish Confederates (University of South Carolina), is over 500 over-sized pages long, and includes 31 pages of bibliography. Rosen seems able to provide biographical data (including kinship ties) for almost every Jewish Confederate. They all get personal attention.

Among the most prominent Jewish Confederates are former U. S. Senators Judah Benjamin of Louisiana and David Yulee of Florida. Benjamin served in President Jefferson Davis’s cabinet throughout the War, as Attorney General, Secretary of War, and Secretary of State. Yulee remained in Florida and tended to railroads there.

Henry M. Hyams served as Lieutenant Governor of Louisiana throughout the War. Abraham Charles Myers served as quartermaster general for the Confederacy from March 1861 until his wife insulted Mrs. Jefferson Davis and Myers was fired by Davis in August 1863. David Camden DeLeon, who resigned his U.S. Army commission when war came, was surgeon general for the Confederate army from May to July 1861, but was relieved from duty.

Simon Baruch (father of Bernard Baruch, the famous financier and presidential advisor of the early 20th century) was a medical student in Richmond when war broke out. He rendered outstanding field service at Second Manassas, South Mountain, Antietam, Gettysburg, and in the Shenandoah Valley. He was twice a prisoner of war, discharged for medical reasons, and then re-enlisted and was serving under Joe Johnston in North Carolina when surrender came in 1865.

Julius Levy of Arkansas and nine other Jewish Confederates died at Shiloh. Julius’s brother, Michael, rose from the rank of private to that of lieutenant. Ezekiel J. Levy of Richmond and his regiment were only 200 yards away from the famous Crater explosion in July 1864, and Levy was promoted to captain for his leadership in turning back the Union assault.

Beyond the several thousand Jewish soldiers and sailors in the rebel armies were civilians in service. Mayer Lehman, a Montgomery merchant, labored hard for the relief of Confederates in northern prisons. (His son, Herbert, would become a New York U.S. Senator and the first Jewish governor of a state.)

Two sisters deserve special notes. Eugenia Levy Phillips, married to an anti-secessionist lawyer and Alabama congressman, was jailed in Washington with Rosa O’Neal Greenhow on charges of smuggling and spying. Freed, she and her family moved to New Orleans, where she encountered the wrath of “Beast” Butler. Imprisoned again, she became a symbol of female resistance.

Eugenia’s sister, Phoebe Yates Pember, a Georgia widow, became famous as a nurse in Richmond’s Chimborazo Hospital (with a 8,000 patients capacity). In one story from her memoir, A Southern Woman’s Story, Mrs. Pember staunched the flow of a pierced artery of a young soldier named Fisher, but a surgeon pronounced it inoperable. Fisher asked how long he had left, and she replied, “Only as long as I keep my finger upon this artery.” He asked her to release it, but she refused. Only when she fainted did the end come for him.

Jewish soldiers died at Seven Pines (7), Seven Days (19), Second Manassas (5), Antietam (7), Vicksburg (6), Chancellorsville (7), Gettysburg (6), Chickamauga (2), the Wilderness (6), Spotsylvania (6), Atlanta (12), Mobile (3), and three at Secessionville (3). They had been neglected in Civil War history, but Robert N. Rosen has corrected that.

comments: mcgeheelt@wofford.edu

copyright 2003, Wofford College, SC

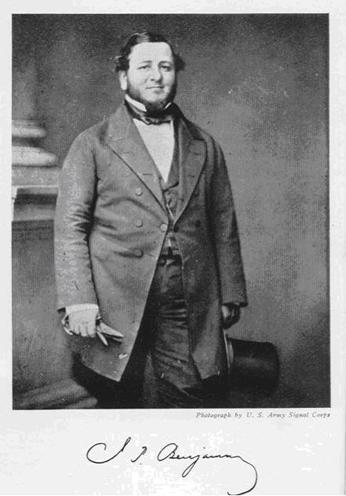

Judah P. Benjamin

"The Brains of the Confederacy"

One of the most misunderstood figures in American Jewish history is Judah P. Benjamin (1811-1884), whom some historians have called "the brains of the Confederacy," even as others tried to blame him for the South’s defeat. Born in the West Indies in 1811 to observant Jewish parents, Benjamin was raised in Charleston, South Carolina. A brilliant child, at age 14 he attended Yale Law School and, on graduation, practiced law in New Orleans. A founder of the Illinois Central Railroad, a state legislator, a planter who owned 140 slaves until he sold his plantation in 1850, Judah Benjamin was elected to the United States Senate from Louisiana in 1852. When the slave states seceded in 1861, Confederate President Jefferson Davis appointed him Attorney General, making Benjamin the first Jew to hold a Cabinet-level office in an American government and the only Confederate Cabinet member who did not own slaves. Benjamin later served as the Confederacy’s Secretary of War and then as Secretary of State.

For an individual of such prominence, Benjamin’s kept his personal life and views somewhat hidden. In her autobiography, Jefferson Davis’s wife, Varina, informs us that Benjamin spent twelve hours each day at her husband’s side, tirelessly shaping every important Confederate strategy and tactic. Yet, Benjamin never spoke publicly or wrote about his role and burned his personal papers before his death, allowing both his contemporaries and later historians to interpret Benjamin as they wished, usually unsympathetically.

During the Civil War, many Southerners blamed Benjamin for their nation’s misfortunes. The Confederacy lacked the men and materiel to match the Union armies and, when President Davis decided in 1862 to let Roanoke Island fall into Union hands without mounting a defense rather than revealing the true weakness of Southern forces, Benjamin, as Davis’s loyal Secretary of War, took the blame and resigned. Anti-Semitism was an unpleasant fact – North and South – during the Civil War years and Benjamin was falsely defamed as having weakened the Confederacy by transferring its funds to personal bank accounts in Europe.

After Benjamin resigned as Confederate Secretary of War, Davis appointed him Secretary of State. Eli Evans, Benjamin’s most perceptive biographer, observed that "Benjamin served Davis as his Sephardic ancestors had served the kings of Europe for hundreds of years, as a kind of court Jew to the Confederacy. An insecure President [Davis] was able to trust him completely because, among other things, no Jew could ever challenge him for leadership of the Confederacy." Near the end of the war, Benjamin privately persuaded Robert E. Lee and other Confederate military leaders that the South’s best chance was to emancipate any slave who volunteered to fight for the Confederacy. When Benjamin repeated this proposal to an audience of 10,000 persons in Richmond in 1864, his remarks lit a firestorm. Georgian Howell Cobb observed, "If slaves will make good soldiers, our whole theory of slavery is wrong." Benjamin’s idea, however valuable, was rejected as politically impossible. As Evans observes, "The South chose [instead] to go down in defeat with the institution of slavery intact."

When John Wilkes Booth assassinated Lincoln in 1865, Davis and Benjamin were suspected of having plotted the event and, as the martyred Lincoln was compared to Christ in the Northern press, Benjamin was pilloried as Judas Iscariot. When the South was defeated, fearing that he could never receive a fair trial if charged with Lincoln’s murder, Benjamin fled to England, where he lived out his life as a barrister, publishing a classic legal text on the sale of personal property. Evans speculates that, had Benjamin been captured by Union troops, the United States might have had its own Dreyfus Trial.

A solitary man, estranged from his wife, Benjamin died alone in England. His daughter arranged to have him buried in the Catholic Pere Lachaise Cemetery in Paris. Until 1938, when the Paris chapter of the Daughters of the Confederacy provided an inscription with his American name, his simple tombstone was engraved with the name "Philippe Benjamin."

While Judah Benjamin preferred such obscurity, his prominence as a Jew assured that he would come under harsh scrutiny during and after his life. For example, on the floor of the Senate Ben Wade of Ohio charged Benjamin, a defender of slavery, with being an "Israelite in Egyptian clothing." With characteristic eloquence, Benjamin replied, "It is true that I am a Jew, and when my ancestors were receiving their Ten Commandments from the immediate Deity, amidst the thundering and lightnings of Mt. Sinai, the ancestors of my opponent were herding swine in the forests of Great Britain."

All contents copyright (c) 1997-2003 American Jewish Historical Society, All rights reserved

* Excerpt from The History of the Jews of Richmond from 1769 to 1917, by Herbert T. Ezekiel and Gaston Lichtenstein, 1917, p. 166.

Though only a war-time resident of Richmond, Judah P. Benjamin stood head and shoulders above any Jew who ever lived in this city. Holding at various times three of the five Cabinet positions within the gift of the head of the “storm-cradled nation,” President Davis was but voicing in a practical manner the sentiment of those who called Benjamin “the brains of the Confederacy.” Whenever there was doubt as to what disposition should be made of some matter, it generally resulted in it being sent to Benjamin. It was not unusual for him to remain at his desk from eight o’clock one morning until four the next. The positions held by him in the Cabinet were: Attorney General, February 25 to September 17, 1861; Secretary of War, September 17, 1861, to March 18, 1862; acting Secretary of War, March 18 to 23, 1862; Secretary of State, March 18, 1862, until the end of the war.

Upon the laying of the cornerstone of the Lee Monument, October 27, 1887, the weather was very inclement, so the speaking incident thereto took place that night in the Hall of the House of Delegates in the Capitol building. The speaker of the evening was Colonel Charles Marshall, who, during the war, had been General R. E. Lee’s military secretary. Colonel Marshall spoke on some of the secret history of the Confederacy. He told one incident of Benjamin that showed him to be as truly patriotic as any citizen who ever lived on this or any other continent. It concerned his resignation as Secretary of War. Early in ’62, General Huger, who was in command of Roanoke Island, then in possession of the Southern forces, made a requisition for powder. It was not sent. A second and third call were likewise ignored, and on February 8th Roanoke Island fell.* Huger complained and in compliance with his request a committee of Congress investigated the failure to send powder. When the investigating body met, Benjamin in a very few words told them why it was not sent—there was not any to send, a temporary shortage of that munition existing. The committee being about to rise, Benjamin asked if it would not have a very harmful effect on the people if the true state of affairs were disclosed. The committee thought it would. The Cabinet official suggested that the report of the committee censure him for not sending the powder. This was done, and to keep up appearances, Benjamin sent in his resignation as Secretary of War. That same day, to the intense disgust of many, the President appointed him Secretary of State, he continuing for five days to act as Assistant Secretary of War. Except to Davis and a few other high officials, the truth of the matter remained secret until 1887. It was his resignation under a cloud that probably caused such a violent dislike in some quarters to Benjamin, a dislike that was only heightened by the promptness with which he was appointed to another portfolio. Colonel Marshall told the writer that he had the incident in a letter from Mr. Benjamin.

*Jewish-Confederate soldier Pvt. Henry Adler of the 46th Virginia lost his life in this battle. LMB.

Immediately overhead, not fifty feet away, a different tribute had been paid the Jew twenty-four years previous. Shortly before Gettysburg, in the early summer of ’63, when the ultimate success of the Confederacy seemed probable, the lower House of Congress was discussing a resolution to remove the Capital to Nashville, Tenn. Henry S. Foote, of that State, in the course of the discussion, remarked that so soon as the independence of the Confederate States was achieved, he proposed to offer an amendment to the Constitution that no Jew be allowed within twelve miles of the Capital. (This of itself amounted to nothing, for Foote was admittedly a “crank,” and for a time seemed to be even worse, he having left Richmond clandestinely and gone North. Finally, however, he returned.) When the Congressman from Tennessee made this remark a wave of applause swept the house.

Benjamin left Richmond on that fateful April 2, 1865, going to Danville with President Davis and other officials. He did not at first stop at Major Sutherlin’s house with the rest of the party. The late Dr. M. D. Hoge, an admirer of the Secretary, to illustrate the latter’s aptness, used to tell this story: On the morning of Sunday, April 9, 1863, the party was at breakfast at Major Sutherlin’s. The lady of the house asked Benjamin what church he proposed attending that day. In reply, he inquired of her where she expected to attend services. Mrs. Sutherlin said that the party was going to hear Dr. Hoge, who was a Presbyterian. The reverend gentleman would smile at this point, saying he recognized the Secretary’s predicament, Cabinet etiquette demanding that he accompany his chief, Davis, who always attended the Episcopal church. Benjamin did not hesitate a second. Quick as a flash he requested: “May I not have the pleasure of escorting you?” which he did.

Benjamin did not return from church with the party, but went to the telegraph office for dispatches. Dr. Hoge says he was sitting in the parlor when the Secretary entered the house, and as he passed the door he nodded to the Doctor to come up to their room. He did so, and was told by the Cabinet official that Lee had surrendered. Dr. Hoge said he did then what he had not done since grown—he laid his head on the pillow on the bed and cried.

That day the entire party left for the South, first by rail, and later by horseback. Midshipman Louis P. Levy, of the Confederate Navy, a mere youth, and a Richmond boy, was of the party. During their ride through the South, Benjamin, rather a short man, rode an extremely tall horse, and notwithstanding the general sadness which hung over the entire country, excited the risibilities of all beholders. He made his way to the coast of Florida and, taking passage in an open boat, succeeded in reaching the West Indies, finally making his way to England. Here he set up the plea that, having been born on English territory, and never having renounced his citizenship, he remained an Englishman. His parents were on their way to New Orleans during the War of 1812 when the ship on which they were was chased by an English vessel. They put in at the Island of St. Croix, and here, on English soil, Judah P. Benjamin was born. His claim of English citizenship being allowed, after a brief probation (to allow him to become familiar with the statute law of Britain) he entered the bar. Shortly afterwards he became a Queen’s chancellor, the only person not born in England who ever held that position. This allows the holder to plead before the House of Lords, which is practically the court of last resort.

On one occasion, Benjamin arguing a case before the Lords, had just begun his brief when some one, supposedly Lord Cairns, who always entertained an extreme dislike for him, ejaculated the single word, “Nonsense!” The Chancellor folded up the brief he had been reading, placed it in his bag and walked out. The Lords did what they had never done before or since. They sent him an apology and asked him to return and finish reading his brief. As he had a right to do, Benjamin had his clerk finish the reading and, incidentally, won his case.

When in compliance with the mandate of his physician, he relinquished the practice of law, he had to return to his various clients over $100,000 of retainers. In his sixteen years of practice at the English bar he earned over $720,000. The entire bar of England tendered him a banquet upon his retirement. He died in Paris on May 6, 1884.

The record of Benjamin in this country was truly wonderful. When United States Senator from Louisiana he declined a seat on the bench of the Supreme court of the United States tendered him by President Pierce. He was counsel for the Government in the Lower California land case, for which he received the largest fee paid for legal services in this country up to that time.

Several years ago* the Jewish citizens of Richmond, at the request of Lee Camp, Confederate Veterans, placed a picture of Benjamin in the gallery of that organization. Philip Whitlock made the presentation, and Rev. Dr. Edward N. Calisch delivered the address on the part of the donors. In the remarks of the latter occurred one sentence that should be reproduced here. “If this man had proven false to his trust the ignominy would have been ours; but as he was a statesman, a patriot and a gentleman, we claim the right to shine in his reflected glory.”

*In the context of when this was written, about 1900.

There be those who seem to delight in claiming that Benjamin was not a Jew, because he took no prominent part in communal affairs. It must be remembered that he was a very busy man, working often, as has been before remarked, twenty hours a day. No less an authority than the late Dr. Isaac M. Wise told the writer that Benjamin delivered an address in the synagogue in San Francisco on Yom Kippur (Day of Atonement), 1860.* It will also be noted that in the letter of Joseph Goldsmith, that in the fall of ’64 when Rev. Michelbacher requested the furloughing of the Jewish soldiers for the holidays, the suggestion was made that the petition be taken first to Benjamin. He being Secretary of State at that time, and the petition referring to a matter solely within the province of the War Department, shows that those in charge of the matter considered Benjamin one of them. Again it has been positively stated by the late Ellis Bottigheimer that he had seen Benjamin “called up” to the reading of the Law at Beth Ahabah Synagogue. Laying all this aside, there yet remains the racial aspect that, being the child of Jewish parents, Judah P. Benjamin was, emphatically, a Jew. All his life he had been known as such, though his wife, a devout Catholic, used every effort to have him affiliate with that church. She apparently succeeded, for on his death-bed he received the rites of her religion. This, it is claimed, had no significance whatever, as he was unconscious at the time. As a young man at Yale he possessed a Hebrew Psalter.

*Bertram W. Korn and Eli Evans have analyzed this statement by Wise, and came to the conclusion that Wise was mistaken. Benjamin was in California at the time, but never attended the synagogue there. He did make a speech at the Church of the Advent, where he appeared in a fundraising event for the case he was conducting at the time. His speech was covered in the San Francisco newspapers, and it may be that Wise, who was very elderly at the time he described this event to Ezekiel, confused a church for a synagogue. Eli N. Evans, Judah P. Benjamin: The Jewish Confederate, Free Press, 1988, p. 95.