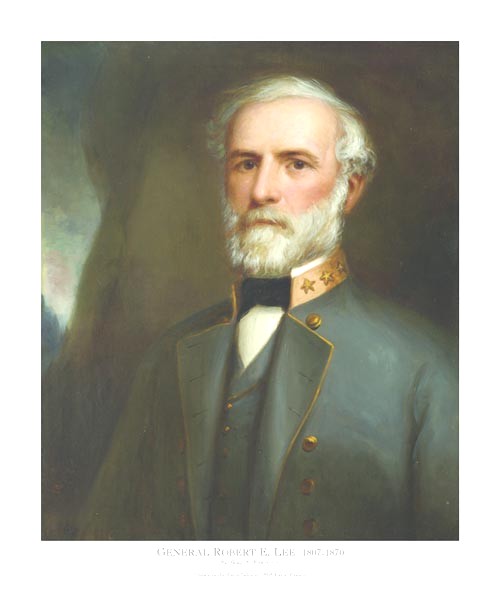

"They say you had to see him to believe that a man so fine could exist. He was handsome. He was clever. He was brave. He was gentle. He was generous and charming, noble and modest, admired and beloved. He had never failed at anything in his upright soldier's life. He was born a winner, this Robert E. Lee. Except for once. In the greatest contest of his life, in a war between the South and the North, Robert E. Lee lost" (Redmond). Through his life, Robert E. Lee would prove to be always noble, always a gentleman, and always capable of overcoming the challenge lying before him.

Robert Edward Lee was born on January 19, 1807 (Compton's). He was born into one of Virginia's most respected families. The Lee family had moved to America during the mid 1600's. Some genealogist can trace the Lee's roots back to William the Conqueror. Two members of the Lee family had signed the Declaration of Independence, Richard Lee and Francis Lightfoot. Charles Lee had served as attorney General under the Washington administration while Richard Bland Lee, had become one of Virginia's leading Federalists. Needless to say, the Lees were an American Political dynasty (Nash 242). Lee's father was General Henry "Light-Horse Harry" Lee. He had been a heroic cavalry leader in the American Revolution. He married his cousin Matilda. They had four children, but Matilda died in 1790. On her death bed she added insult to injury upon Henry Lee by leaving her estate to her children. She feared Henry would squander the family fortune. He was well known for poor investments and schemes that had depleted his own family's fortune (Connelly 5).

Henry Lee solved his financial problems by marrying Robert's mother Anne Carter, daughter of one of Virginia's wealthiest men (Nash 242). Henry Lee eventually spent his family into debt. Their stately mansion, Stratford Hall, was turned over to Robert's half brother. Anne Lee moved with her children to a simple brick house in Alexandria. Light Horse Harry was seldom around. Finally, in 1813 he moved to the West Indies. His self-exile became permanent, and he was never seen again by his family (Thomas).

Young Robert had other family problems. His mother became very ill. At the age of twelve he had to shoulder the load of not only being the family's provider, but also his mother's nurse. When time came for Robert to attend college, it was obvious his mother could not support him financially. She was already supporting his older brother at Harvard and three other children in school. In 1824 he accepted an appointment to the United States Military Academy. During his time at West Point Lee distinguished himself as a soldier and a student. Lee graduated with honors in 1829 (Nash 245).

His graduation was dampened by a call to the bedside of his ailing mother. When he arrived home he found his fifty-four year old mother close to death. A death caused by struggles and illnesses of her difficult life. Robert was always close to his mother. He again attended to her needs until her death. On July 10, 1829, Anne Lee died with Robert, her closest son, at her side. Forty years later Robert would stand in the same room and say, "It seems but yesterday" that his beloved mother died (Connelly 6).

While awaiting his first assignment, Lee frequently visited Arlington, the estate of George Washington Parke Custis. Custis was the grandson of Martha Washington and the adopted son of George Washington. After Martha's death Custis left Mount Vernon and used his inheritance to build Arlington in 1778. Arlington was set on a hill over looking the Potomac river and Washington D.C. (NPS Arlington House). Custis had only one daughter, Mary Anna Randolph. Mary had been pampered and petted throughout her life. Lee's Courtship with Mary soon turned serious, before long they were thinking of marriage. However, before Robert could propose he was assigned to Cockspur Island, Georgia.

Robert returned to Arlington in 1830. He and Mary decided to get married. The two were married on June 30, 1831(Nash 248). Shortly there after the Lees went to Fort Monroe. Mary was never happy here. She soon went back to Arlington. Mary hated army life. She would, for the most part, stay at Arlington throughout the rest of Robert's time in the United States Army. The fact that he was separated from his family, and that he was slow to move up in rank, left Lee feeling quite depressed a great deal of the time. Over the next decade Robert became very frustrated by his career and life. Lee's life had become a mosaic of dull post assignments, long absences from family, and slow promotion. Lee began to regard himself as a failure (Nash 248). Lee was on the verge of resigning from the army all together, when on May 13, 1946, word came that the United States had declared war on Mexico.

The outbreak of war with Mexico provided Lee his first real chance at field service. In January of 1847 he was selected by General Winfield Scott to serve with other young promising officers. These officers included: P.G.T. Beauregard and George McClellan on his personal staff (Connelly 8). During the Mexican War Lee won the praise and respect of Scott as well as many other young officers that he would serve with and against later.

As the years passed Mary Lee was left at Arlington. She was left to manage her fathers grand estate, plantation really, by herself. Time had taken its toll on Mary Lee. She had become an ageing woman, crippled with arthritis, and left alone by her career Army officer's duty assignments elsewhere (Kelly 39). At the news of his father-in-laws death, Lee was able to take official leave and hurry home. Upon his arrival he was shocked by the state of his wife's health. As she herself had written to a friend, "I almost dread his seeing my crippled state"(Kelly 39). Lee was able to extend his leave indefinitely. He became, in essence, a farmer. He was still able to some duties in the army. These usually involved dull service such as a seat on a court-martial. However, there was one such duty that proved to be much more important. In October of 1859 he was sent to quell John Brown's bloody raid at Harpers Ferry (Grimsley). In the nations capital, setting just below Arlington, there were heated debates over states' rights union verses disunion, and slavery. All the salons of Congress and in the salons and saloons of the politically charged capital city, there was debate (Kelly 40).

After three years at home, Lee finally had to return to full time Army duty. He was posted in Texas. While Lee was in Texas the controversy over states' rights grew worse. On January 21, 1861 five Southern Senate members announced before a packed audience in the Senate galleries that their respective states had seceded. With that, each gathered their things and departed. Soon Texas seceded too, and Lee was ordered home to Washington, to report to the Army's ranking officer, General Winfield Scott. Lee arrived at Arlington on March 1st. He now faced a very momentous personal decision. After the firing on of Fort Sumpter, the first shots of the Civil War, Lee was offered command of the Federal Army by Abraham Lincoln. Lee was offered command of an army that was charged with the duty of invading the South. A south that included Virginia, a Virginia that Lee truly loved. On the morning of April 19th, Lee returned from nearby Alexandria with news that Virginia to had seceded. The Lees had their supper together. Lee then went, alone, to his upstairs bedroom. Below, Mary listened as he paced the floor above, then heard a mild thump as he fell to his knees in prayer. Below, she also prayed (Kelly 41).

Hours later he showed her two letters he had written. In one he resigned his commission in the United States Army. In the other, he expressed personal thoughts to General Scott. Later, his wife would write: "My husband has wept tears of blood over this terrible war, but as a man of honor and a Virginian, he must follow the destiny of his State" (Kelley 41).

Only two days after his resignation from the United States Army, Lee travelled to Richmond to accept his commission as a General in the Confederate army J. Davis-Papers). Lee's impact was felt immediately on the confederacy. As a seasoned military strategist, he brought the most comprehensive, technologically advanced knowledge of warfare to bear against his own former army (Nash 257).

General Lee's first campaign in what was to become West Virginia was not a great success. Command of the Eastern Army was divided between the hero of Fort Sumpter, P.G.T. Beauragard, and Joseph Johnston who together won the first big battle of the East, Bull Run. Thus Joseph Johnston was in command when George B. McClellan started his march on Richmond. When Johnston went down with wounds it was easy for Davis to replace him with General Lee. Lee immediately took charge and attacked, trying to make up for his numbers with audacity. He drove the Union army back about 25 miles, but was unable to destroy it in a series of continuous battles known as the Seven Days Battle.

In September of 1862, McClellan attacked Lee at the Battle of Antietam. McClellan attacked Lee but failed to break his lines. Lee, realising that he was in a dangerous position and far from his supplies, retreated and took up a defensive position behind the Rappangonnock River in northern Virginia. Here General Ambrose E. Burnside, who succeeded McClellan, attacked Lee in December at the Battle of Fredricksburg and met a bloody repulse. As the year of 1862 closed, Lee had given the Confederacy its greatest victories and had become an idol of the Southern people (Comptons).

Lee's Greatest victory was the Battle of Chancelorsville in May of 1863. Lee was faced with a larger army led by fighting Joe Hooker. Lee and his most trusted lieutenant, General "Stonewall" Jackson, divided their forces and through a forced march around General Hooker fell on his exposed flank, rolling it up, and defeating the Union forces yet again (Brinkley 404). After Chancellorsville, Lee started an offensive movement he hoped would win the war, an invasion of Pennsylvania. This led to the greatest land battle in the Western Hemisphere, Gettysburg. The Army of Northern Virginia led by Lee, and the Army of the Potomac led by General George Meade, hammered each other for three days. On the 3rd day of battle General Lee hoping to end the war ordered the great frontal assault popularly known as Pickett's Charge. The attack was a huge failure (Brinkley 405). Lee blamed only himself.

For the next two years, Lee commanded an Army that was poorly supplied and getting increasingly smaller. Lee had to go on the defensive. He inflicted heavy losses on Grant at the battles of The Wilderness, Spotsylvania, and Cold Harbor (Brasington).

By April 9th 1865 Lee had no choice but to surrender to Grant. Lee met Grant at Appomatox Courthouse. As Grant walked in the meeting room, wearing a dusty privates uniform, he must have been humbled by the man who rose to greet him. Lee was wearing a noble grey uniform with a polished sword at his side. Grant and Lee then decided on the terms of the surrender. Lee asked Grant if his soldiers could keep their horses. Grant answered, "I insist upon it." As Lee rode back to his camp, Confederate troops surrounded him saying, "General are we surrendered? They vowed to go on fighting (Nash).

After the war many men came to Lee and said: "Let's not accept this result as final. Let's keep the anger alive." Lee answered by saying, "Make your sons Americans." When the war was lost Robert E. Lee took a job as president of Washington College, a College of forty students and four professors. Over his time he had trained thousands of men to be soldiers, and had seen many of those thousands killed in battle. Now he wanted to prepare forty of them for the duties of peace (Redmond).

Works Citied

Robert E.

Lee:

The Engineer

By Andrew Price

Robert E. Lee's military genius and battlefield success are renowned. Over the years, scholars have analyzed these aspects and drawn conclusions about Lee ranging from a brilliant general to one who lost the war for the South. Lee's fatherless childhood and excellent West Point education have also been considered as overriding factors in his success as a military commander. However, little or no attention has been paid to the general's engineering career. From the time he decided to pursue a West Point education and an engineering career, Lee focused on absorbing every detail associated with military engineering. Although many factors of Lee's life have been cited as reasons for his leadership style and military actions, Robert E. Lee's engineering background and education ultimately determined his military leadership style.

Robert's engineering education began with West Point. Due to his love of practical sciences and his need for a steady income, Robert had always leaned toward a career in military science (Long 27). In February of 1824, Robert and his family decided to throw their collective weight into attaining an appointment for him as a cadet (Thomas 42). After much lobbying, Robert received an appointment to West Point from John C. Calhoun. Over a year later, in July 1825, Robert was finally admitted to the college (Thomas 43). Before entering West Point to pursue military science, Robert attended a preparatory school in the winter of 1824-25 to refresh his studies (Long 27). Robert's schoolmaster Hallowell rewarded him with a glowing report for his promptness and attention to detail (Thomas 43-44). Throughout Robert's difficult courses at West Point, he continued to receive seamless reviews concerning his flawless student conduct. During his four years, Robert narrowed his focus and studies to become a military engineer for the Army Corps of Engineers. Among his final classes were field fortification, permanent fortification, artillery, grand tactics, and civil and military architecture (Thomas 51). These courses would not only assist him in his future engineering projects, but ultimately provide him with specific battlefield knowledge he would use during both the Mexican-American War and the Civil War. After four years at West Point, Robert graduated second overall in the class of 1829, without receiving a single demerit, and with a remarkable balance of $103.58 (Thomas 52-54). Due to the cadets' low allowance, any positive balance after four years at West Point was rare. However, Robert's frugality allowed him to not only stay out of debt, but to make money during his time there. Although he now had money, the engineering career awaiting him was less profitable, financially.

The next chapter of Robert E. Lee's life is perhaps the most tedious; however, Lee's numerous projects for the Army Corps of Engineers provided the experience-based knowledge he needed to supplement his extensive factual education. These projects spanned from 1829 to 1855, during which he slowly climbed the ladder in rank (Did You Know?). Upon entering the Corps, Lee became brevet second lieutenant in the Army Corps of Engineers due to his outstanding performance during college (Thomas 54). His first assignment dealt with fortification work on Cockspur Island in Savannah, Georgia (Thomas, Macmillan, 320). Here he worked as an assistant engineer under Major Babcock, who, after overriding Lee's plan for the wharf's location, failed to return for the second year of construction. After surveying what damage the summer off-season had dealt the first year's construction, Lee realized that his plan for locating the wharf would have succeeded, despite the older engineer's opinion. Then, just as Lee finished preparing the site for reconstruction according to his plans, the Army Corps of Engineers sent Lieutenant Joseph K. F. Mansfield, and later Captain Richard Delafield, to replace the absent Babcock. They soon devised their own plan for the fortifications, and Lee was once again overruled by his senior engineers (Thomas 57-63). Following this shift in engineers, the Corps quickly realized their overstaffing of the project and relocated Lee to Fort Monroe, Virginia. During his stay at Fort Monroe, Lee managed his first project on his own. Though the tasks were not particularly challenging, they did require constant attention. Moreover, his simultaneous management of all affairs and projects at Fort Monroe began to show the Army his leadership potential. Subsequently, they made Lee a bona fide second lieutenant. However, perhaps because of the routine nature of the work, Lee wrote his brother, "I suppose I must continue to work out my youth for little profit and less credit & when old be laid on the shelf" (Thomas 67-69). After only three years in the service, Lee was already expressing his frustration with the slow promotion within the senior dominated Army Corps of Engineers, during peacetime operations.

As the monotonous work continued, Lee requested a reassignment, something closer to Arlington. He was granted an office job in Washington, which he readily accepted (Thomas 75). This job did little to improve Lee's engineering abilities, besides organization. It mainly served only as a window through which he saw the inherent problems associated with the Army Corps' Washington connection. At first, he relished being the lobbyist for the Corps of Engineers; however, the meticulous job of accounting and record keeping soon depleted his initial enthusiasm (Thomas 81). In the spring of 1835, Lee's repetitive daily cycle was broken when he was assigned to accompany his old-time superior and friend Andrew Talcott on a surveying mission. Apparently, a border dispute had erupted between Ohio and the Michigan territory. The Corps of Engineers was to dispense an engineering team to survey the line and quickly end the dispute (Freeman 1: 133). Though Lee's time trekking the northern woods is often considered simply a relief from his desk, this summer trek undoubtedly prepared him for future scouting work, and sharpened his ability to accurately judge and analyze the lay of the land. Moreover, Lee's ability to succeed in yet another project finally caught the attention of his superiors. This prompted Lee's promotion to a job that would truly test his abilities.

At the pinnacle of Lee's engineering career, he headed surveying and redirection of the Mississippi River at St. Louis. Upon arrival, Lee was presented with several challenges: survey the Rock Island Rapids, make plans of recommendation for their improved navigability, analyze the Mississippi's change in course away from the city, and create a plan to redirect the Mississippi River and restore the city's harbor (Thomas 86-87). Lee and his assistant Second Lieutenant Meigs first surveyed and drew up plans for the Rock Island Rapids before directing their efforts toward the St. Louis harbor. After surveying the harbor, Lee devised an ingenious plan to use the Mississippi to reestablish a deep-water harbor and permanently redirect the river (Freeman 1: 146-147). Funds were approved and construction of the first dyke commenced. Within a year, the project's fruits were such that boats could once again reach the harbor (Freeman 1: 152). Subsequently, a dispute in the city arose over the continuation of funding to finish Lee's plan (Sanborn 82). Once tempers cooled, funding was restored for the 1839 construction year. Lee continued construction until an Illinois injunction against the Army forced Lee to halt work. He then arranged for the city of St. Louis to use government equipment to continue construction (Freeman 1: 44). Although Lee abstained from voicing an opinion during the two conflicts, they only proved to further his dislike and frustration with politics and their control over his time sensitive work (Sanborn 82-83). Lee joined Lieutenant Horace Bliss at the rapids to finish preliminary rock removal, ending the work season of 1839 (Sanborn 88). The injunction was lifted at the beginning of 1840; however, citing the apparent success of the project, both the municipal city government and Congress failed to appropriate additional funding to finish Lee's plans (Thomas 97). Subsequently, Lee was forced to return to St. Louis, survey and assess the progress of the unfinished project, close company accounts, and sell all the machinery. Though Lee met the discontinuation of his project with great sadness, his system of dikes and plans for the rapids were eventually seen through and are still used today to control the Mississippi around St. Louis (Sanborn 93). Concerning Lee's four years of labor on the rapids and St. Louis project, Mayor Darby wrote:

By his rich gift of genius and scientific knowledge, Lieut. Lee brought the Father of Waters under control.... I made known to Robert E. Lee, in appropriate terms, the great obligations the authorities and citizens generally were under to him, for his skill and labor in preserving the harbor... One of the most gifted and cultivated minds I ever met... The labors of Robert E. Lee can speak for themselves (Freeman 1: 182-183).

Indeed, Lee seemed to have such an effect on all those with which he worked; he returned home "an engineer of recognized reputation" (Freeman 1: 182). Perhaps the greatest quality Lee took from the four years on the St. Louis project was the ability to deal with public opinion. The next six years of Lee's life consisted, professionally, of routine inspections of forts and filing reports for repairs on each (Thomas 101). During which, Lee was never able to surpass his labors performed in Saint Louis. More immediately, "the fact remained: the opportunities that were to come to him in Mexico were created at Saint Louis" (Freeman 1: 182). Lee's opportunities, both in being assigned to and successful in Mexico, originated from his tedious labors during his years of service in the Army Corps of Engineers.

During Lee's service in the Mexican War, he gained additional battlefield experience and used his collective knowledge to impress his commanding officers. Once war broke out in Mexico and troops left for action, Lee found that his chance for success and promotion lay in Mexico. On August 19, 1846, Lee was ordered to turn his work at Fort Hamilton over to Major Richard Delafield and report to Brigadier General John E. Wool for service as a field engineer in Mexico (Freeman 1: 202). After preparing bridges and roads for the initial advance of Wool's troops across the Rio Grande, Lee remained idle for three months as Wool awaited orders. Lee was then transferred to Brazos Santiago where he joined General Winfield Scott (Sanborn 108-112). The Army had made this transfer in order to use Lee's talents to assist Scott in the Vera Cruz expedition. However, Lee needed such an opportunity to prove his abilities for praise and promotion from his superiors. "Although he didn't know it, he had started up the ladder of fame" (Freeman 1: 219). The first rung of this ladder would be climbed as Lee transferred his engineering, and all other, services to assist General Scott in a quick and decisive war victory.

From Brazos Santiago, Lee traveled with his commanding officers and fellow engineers to Vera Cruz where, under Lee's direction, batteries were set up to lay siege on the city (Sanborn 113-115). Throughout this first engineering task conducted under fire, Lee displayed resilience as he ordered disgruntled sailors to continue digging the batteries (Freeman 1: 230). Though Lee received little praise for his direction in the successful siege, he undoubtedly found his resolve during the battle self-gratifying. From the Mexican armaments at the conquered Vera Cruz, Scott's troops refitted and moved inland toward Mexico City (Freeman 1: 233-234). Here they found the road blocked by Santa Anna's army, which was positioned in a series of defensive lines. While the expedition set up camp two miles from the Mexican lines, Lee was charged with finding a weakness in the enemy's position (Thomas 125). Along the National Road lay the Mexican batteries. To their right was a cliff which was, according to Lee, "unscalable by man or beast" (qtd. in Sanborn 117). Noting this, Lee turned his attention to the impassable ravines to the left of the Mexican lines. After a day of reconnaissance, mostly spent hiding under a log from Mexican soldiers, Lee confirmed that the ravines could be navigated by an army (Thomas 125-126). From his scouting, General Scott formulated a plan to flank the Mexican lines from the ravines while simultaneously launching a frontal assault, thus pinning the Mexican forces against the river. This plan proved so effective that Santa Anna himself barely escaped; moreover, he left behind official papers, topographical maps, and letters addressed to members of Scott's army (Thomas 127). Lee would later use these papers and topographical maps to base future battle strategies (Thomas 128). The Battle of Cerro Gordo truly enhanced Lee's standing as an engineering officer. From it he received three glowing reports from General David E. Twiggs, Colonel Bennett Riley, and General Winfield Scott concerning Lee's valuable performances during the expedition (Freeman 1: 247). Eventually, more praise would resound from Lee's superiors, as more doors of opportunity would open for him, throughout the war.

As the war progressed, Lee's amazing feats of reconnaissance proved to further his superiors' view of him as a capable soldier (Freeman 1: 271-272). In fact, the greatest loss of life during the entire campaign came upon an attack of fortifications lying on the plane leading up to Mexico City. Here Lee had taken no part in tactical decisions; furthermore, a lack of reconnaissance was cited as the key failure in preventing heavy casualties during the battle (Freeman 1: 275, 297). Though Lee served alongside many officers with or against whom he would fight in the coming Civil War, his greatest profit was the twenty months he had spent learning realistic battlefield tactics, army leadership organization, the importance of reconnaissance, and audacity (Freeman 1: 296, 297). These basic military skills he had learned from the renowned military leader General Winfield Scott, and had combined and compared them with the theoretical information acquired at West Point to put together a solid military beginning (Freeman 1: 250). However, the much larger scale operations of the Civil War would force Lee to draw from his every experience and ounce of knowledge to create a military leadership style unlike any other, one capable of defending Virginia through duty and compassion for its people.

From the time he organized the volunteer Army of Northern Virginia, to his surrender at Appomattox, Lee used his former education and experience to make his decisions on the battlefield. While others inherited armies, Lee built one (Bradford 190). After resigning from the United States Army, Lee accepted the Virginian offer of major general on April 23, 1861. Then on August 31, 1861, Lee was appointed to Confederate generalship under Samuel Cooper and Albert Sidney Johnston (Gallagher 1154). Due to a wound Joseph E. Johnston received on the first day of the Seven Days Battle, Confederate President Davis appointed Lee to lead the Army of Northern Virginia (Gallagher 1155). After a year of desk jobs organizing and creating defenses for the Confederacy, Lee finally got his army; the one he had built (Bradford 100).

Lee went about commanding his army with the care he had employed as an engineer supervising his work crews. In the fatherly care he had for his troops, Lee often gave his own food to the infirmary (Sanborn 366). In addition to this, he was often down among the soldiers shaking hands and giving words of hope (Sanborn 261). This was all just as Lee had done with his workers on his previous engineering jobs, where he would go to the work site and even eat lunch side by side with them. Both on the battlefield and on the job site, his goal was to get a feel for their work and assist them in any way possible. Likewise, Lee organized his army as he had his engineering teams, compact and efficient. All officers who were not fulfilling orders were removed and reassigned (Thomas 256). Militarily, this may not have been the best decision, due to the possibility an irreplaceable officer could be killed in combat; however, this was Lee's method. As Lee had done in every project and military battle, he would gather all details for analysis. Then, before making plans concerning any situation, Lee considered all factors, including: topography, condition of men, weather, time of year, etc. In addition to details, Lee formulated complicated plans that depended heavily on his subordinates to carry through (Freeman 2: 241). On engineering projects, Lee was able to closely monitor such subordinates and correct their errors. However, on the battlefield, failures to carry out all parts of Lee's plans often resulted in the loss of a battle. Defending Lee as a general, General Gordon once said, "Lee could not be beaten! Overpowered, foiled in his efforts, he might be, but never defeated until the props which supported him gave away..." (qtd. in Bradford 175). Lee's attention to detail enabled him to formulate plans that, when properly executed, would prevail against any traditional military tactic, even in the face of staggering odds.

Although many factors have been cited as reasons for Robert E. Lee's leadership style and military actions, his engineering background combined with his education and experience ultimately determined his military leadership style. Lee's methods and strategies were not necessarily traditional, but his wealth of experience and knowledge combined with his military genius allowed him to devise successful plans for his poorly equipped army. Throughout his life, Lee made such decisions as to allow doors of opportunity open along the way, and he surely made the most of these, as he had originally only wanted to be an engineer.

Works Cited

Bradford, Gamaliel. Lee the American. Boston: Houghton, 1912.

Did You Know? No. 33. Office of History, US Army Corps of Engineers. 11 November 2004 <http://www.hq.usace.army.mil/history/vignettes/vignette_33.htm

Freeman, Douglas Southall. R. E. Lee: A Biography. 4 vols. New York: Scribner's, 1934-35.

Gallagher, Gary W. "Robert E. Lee." Encyclopedia of the American Civil War. Ed. David S. Heidler and Jeanne T. Heidler. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, 2000.

Long, A. L. Memoirs of Robert E. Lee. 1886. Secaucus, NJ: The Blue and Grey Press, 1983.

Sanborn, Margaret. Robert E. Lee A Portrait. 1966. Moose, WY: Homestead Publishing, 1996.

Thomas, Emory M. "Robert E. Lee." Macmillan Information Now Encyclopedia: The

Confederacy. Ed. Richard N. Current, et al. New York: Simon, 1993.

- - - . Robert E. Lee: A Biography. New York: Norton, 1995.

Lee: The Educator

For the current generation of Americans, as the sectional controversies of the Civil War are all but obliterated, the name General Robert E. Lee summons the image of the venerated vanquished war hero, idolized as a noble symbol for the Lost Cause. Yet it is often said that our true characters are most unambiguously revealed when we teach others. Although Lee is one of the most celebrated generals in American history, it is his postwar career as the President of Washington College (now Washington and Lee University) and his achievement as an amazingly worthy educator that illustrate his true character. As a man, Lee’s profound Christian faith allowed him to develop a personal moral code focused on duty, kindness, diligence, and self-denial. His military experience, both as a war commander and as a brilliant student at West Point, ingrained in him the importance of duty – obedience and self-denial for the greater good. Uniting the moral concepts he derived throughout his life, Lee transformed Washington College into an experience that attempted to educate students as well as elevate their moral standards; in other words, Lee’s actions as President of the college tried to develop the students’ intellectual and moral potential to allow them to become gentlemen. Through these achievements, Lee showed his own moral standards by setting a personal example for his students and by attempting to reconcile sectional differences with the North and rebuild the ravaged South.

Lee’s fascination with education can be traced from his years as superintendent of West Point Military Academy in the early 1850s. However, it was at Washington College that Lee showed his aptitude as a great educator and made groundbreaking changes in the academic programs in an effort to revitalize the decrepit college and revolutionize outdated antebellum systems. Lee could see, even as a commander in battle, that the utmost postwar priority was to educate young Southerners appropriately for the needs of the next few decades. Instead of coercing students into predetermined curricula, Lee changed to an elective system that would allow students to learn from a wide variety of applied subjects, including engineering, mining, chemistry, accounting, business law, photography, and journalism. Lee’s innovative elective system was one of the first established in the country, and his school of journalism was the first of its kind in the world.[1] Lee had concocted a defined plan which he administered very efficiently to improve the various departments and teaching quality at the school, “to establish and perfect an institution which should meet the highest needs of education in every department… Under his advice, new chairs were created, and professors called to fill them… before the end of the first year the faculty was doubled… a completed system of ‘schools’ was established and brought into full operation.”[2] Yet even though Lee was a fervent advocate for technical education necessary for the South’s Reconstruction projects, he often expressed deep regret at not having completed a proper classical, liberal arts education before attending West Point. An Aristotelian at heart, Lee believed in a balanced coalescence of the “scientific” and the “professional studies.” [3]

Fully conscious that intellectual abilities must be explored to full potential by a practical and diverse curriculum, Lee aimed to create such a college where every student could find his proper calling. In fact, his efforts were so successful that Professor Joynes claimed in the college’s University Monthly, shortly after Lee’s death, that “the standards of scholarship were [so high that] soon the graduates of Washington College were the acknowledged equals of those from the best institutions elsewhere, and were eagerly sought after for the highest positions as teachers in the best schools.”[4] In fact, Lee’s meticulousness in monitoring the intellectual development of students was so great that he “watched the progress of every class, attended all the examinations, and strove constantly to stimulate both professors and students to the highest.”[5] He actively interacted with all departments and insisted on staying through semester examinations with the students, often testing them on their knowledge. During his tenure, Lee scrupulously administered and supervised the academic cultivation of young minds at the college, never relenting in his emphasis on pragmatist education for the “rising generation” that would be responsible for “the restoration of the country.”[6] Here, Lee set an example by underscoring intellectuality and practical learning for his students.

Nevertheless, Lee’s achievements in the intellectual sector of the Washing College were only the basis upon which he built an infrastructure of moral learning. As a progressive educator, Lee only rarely used presidential authority as a means for educating. Rather than brute enforcement like he experienced in his military education, Lee tried to impress upon his “boys” moral principles through experience and example. For instance, he once told a young teacher that “as a general principle… you should not force young men to do their duty, but let them do it voluntarily and thereby develop their characters. The great mistake of my life was taking a military education.”[7] To an entering student, Lee wrote that there was only one rule at his college: “that every student must be a gentleman.”[8] Lee incorporated the insights he had gained from his own life into moral principles that he inculcated into his charges. According to Freeman, a prominent Lee biographer, Lee’s own Christian values extended into his moral precepts to make kindness, humility, duty, and self-denial and control the most significant aspects of his character. Although General Lee never lectured his young men about these moral principles, he tried to teach them these gentlemanly virtues through example. Lee’s actions as President of Washington College demonstrate a high awareness and strict observance of these principles.

First, Lee showed considerable kindness in his interactions with the nearly 400 students at the college. Although not impervious to the use of authority, Lee was far from the stern, removed administrator. He personally welcomed every new student in his office and always managed to remember all of his students by name and even “write to the parents of each boy a letter, sometimes in his own handwriting, about once a year, concerning the young man’s conduct,” according to Graham Robinson, a former student.[9] Another anecdote also seems to substantiate the claim of Lee’s amazing memory for student names and records. Captain Rob Lee, Jr., General Lee’s son, recalls that his father heard an unfamiliar name during a faculty meeting and reproached himself for having forgotten the student because he thought he knew every one in college. However, further investigation showed that the student had only recently enrolled while Lee was absent and that Lee had never seen the new student.[10] Yet only knowing the students by name and individual characters was not enough. Lee allegedly knew everything about every student, reviewing their weekly grades and discussing with the students their strengths and weaknesses. His ultimate goal was to help: “If a student needed a place to study, the president let him use a little office near his own. If he had personal problems, he knew where to find a sympathetic listener.”[11] Lee appeared “almost motherly” to his students because of his kindness towards each individual student and willingness to help.

Secondly, humility was another value that Lee demonstrated with his actions at Washington College. A member of his faculty, Colonel William Preston Johnston, fondly recalls that when interacting with the faculty, Lee was “courteous, kind… We all thought he deferred entirely too much to the expression of opinion on the part of the faculty.”[12] Lee never presumed to impress his opinions on others; in fact, he rarely made speeches before the faculty members and rather preferred to listen. According to Fishwick, Lee was at once a pupil and a president and showed, “day by day, the humility which was his true strength… an office [was] a battlefield [where] he had to conquer not opposing armies, but himself.”[13] For many, Lee’s success as educator was a greater triumph than Lee’s achievements as military warrior because of the great humility that he exemplified.

Thirdly, Lee’s sense of duty guided him throughout his career as President. Though his heart condition had been exacerbating continually since 1863, weakening his physical condition, Lee worked incessantly and painstakingly during his tenure.[14] Lee tried to convey the importance of work ethics and diligence to the students by rewarding those who worked uncommonly hard and reprimanding indolence. “My only object is to endeavour to make them see their true interest, to teach them to labour diligently for their improvement, and to prepare themselves for the great work of life,” said Lee, who believed that individuals had the capacity to master evil and implement with moral code with honor and diligence.[15] With duty also came self-discipline. One of Lee’s favorite sayings was “Obedience to lawful authority is the foundation of manly character,” indicating his belief for the importance of maintaining discipline as part of duty.[16] Although Lee was kind in his interaction with students, when they transgressed this moral code and were derelict in duty and discipline, his enforcement of the rules was ruthless and unrelenting. Towards students who did not exert their best efforts and did not observe their duties, Lee was firm in their punishment. [17] Personally, Lee believed in “a true glory and a true honor: the glory of duty done – the honor of the integrity of principle,” a principle that he tried to instill in the morality of his boys.[18]

Lastly, Lee’s self-denial and control was perhaps one of the most important values he tried to pass on to his students. As president, his own behavior exemplified self-control, with an attitude that combined “dignity, decorum, and grace… No matter how long or fatiguing a faculty meeting might be.”[19] Many faculty members expressed a certain feeling of awe for Lee because of this astonishing self-control. To the students, Lee constantly cautioned them against the dangers of alcohol, waging war on liquor because he had perceived its detrimental effects in his army. Lee followed his own advice at social price (though in his case it was small); in regards to sexuality, Lee’s caveat was to “hold on to your purity and virtue.”[20] Lee’s belief in good conduct as well as self-control compelled him to look to the greater good of the South and help defend law and order. In the various heated and violent breakouts in Lexington against the newly freed African-Americans, whatever his own private position was, Lee always cooperated with local authorities to maintain law and order at his college. Lee often appealed to young men’s sense of honor and self-respect to mitigate tension and appease ruffled students during political riots. In one case, when a twelve-year-old verbally abused a black man, Johnston, in Lexington and was shot to death by him, some Washington College students’ turned to violence and threatened Johnston. The leader of the students, Gordon, was arrested and immediately dismissed from the college. Lee’s anger at this upheaval was great, for he believed that “only men of degraded character could commit such violent political crimes.”[21] These kinds of uncontrolled actions were the anathema to the ideal of the gentleman and morality that Lee advocated, which propelled him to take firm disciplinary actions against them. Even though Lee, like his fellow Southerners, echoed the prevailing abhorrence for the military occupation of the South, he showed remarkable self-control in cooperating with the authorities in each of these cases to defend the law and order, even if it meant working with the occupation forces.[22] Though personally opposed to Reconstruction, Lee never succumbed to cries for lynching that permeated in the South and hoped to remain an educator that would set an acceptable example for his students. Even though a significant part of Washington College students were opposites of the gentleman ideal that Lee urged, these “hot little southerners” could not abuse power at his college, thus allowing Lee to become a symbol of nobility of spirit in the white South.[23] Throughout his career as President, Lee exercised great discretion and prudence in his conduct and set an example of morality, exemplified in kindness, humility, duty, and self-denial and control, making him a very praiseworthy educator.

Yet Lee was not the perfect educator. As much as he advocated his cardinal rule of educating his students to behave like gentleman fit for their station, Lee did not believe that every youngster had the potential. He selected his students mainly from the Southern gentry class to which he belonged. In 1865, Lee lucidly states these intentions in a letter to John B. Baldwin, Speaker of the Virginia House of Delegates, proclaiming that young gentlemen ought to study “the most elevated branches of science and literature. But this character of instruction is required by the few; men of high capacity… not for the many; nor is it needed for the industrial classes, who have neither the time nor opportunity for acquiring it.”[24] The student body consisted primarily of young gentlemen from Lee’s class, who could be refined and improved to become leaders in the New South. Although Washington College was non-denominational, Lee’s insistence on Christian values made educating these young men without Protestant Christian influence ineluctable. According to Fellman, “Washington College was to be another expression of the kind of ecumenical, institutionalized Protestant piety that Lee had sought to apply to his army and to the Confederacy.”[25] Although Lee promoted reconciliation efforts and consistently avoided any political association in public to overlook sectional differences during the Civil War and work on rebuilding the South, his deep-rooted habits and beliefs could not be eradicated – he continued to believe in white supremacy, along with many others in the South and in the entire nation, and the inferiority of classes below his own.

However, it would be foolish to deny Lee’s achievements as an outstanding educator. Lee brought new life to the failing Washington College, which now bears his name as a tribute for his contributions to the college. Lee’s efforts to reform education to unite practicality with theory, his own strict adherence to the ideal gentleman’s moral code, his moral influence on the college, and his conscious efforts to work toward reconciliation and reconstruction of the South can all be seen clearly through his work as the President of Washington College. As one of the most enigmatic figures in American history, Lee’s life has been retold as a tapestry interwoven with controversy. Yet as an educator, Lee’s contributions to educating the new generation are undeniable. Whatever his own pretensions or beliefs, Lee was able to overlook those sectional disputes and worked actively toward reconciliation through education. The advice he gave to a Confederate widow effectively sums up his philosophy as an educator: “Do not train up your children in hostility to the government of the United States. Remember, we are all one country now. Dismiss from your mind all sectional feeling, and bring them up to be Americans.”[26]

Selected Bibliography

Primary Sources

Lee, Robert E., Jr. Recollections and Letters of General Robert E. Lee. New York: Konecky & Konecky, 1991.

Gallagher, Gary W., ed. Lee: The Soldier. Lincoln, NE: U of Nebraska Press, 1996.

Connelly, Thomas L. The Marble Man: Robert E. Lee and His Image in American Society. New York: Knopf, 1977.

Fellman, Michael. The Making of Robert E. Lee. New York: Random House, 2000.

Fishwick, Marshall W. Lee: After the War. Westport, CT: Greewood Press, 1963.

Flood, Charles Bracelen. Lee: The Last Years. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1981.

Freeman, Douglas Southall. Lee of Virginia. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1958.

Freeman, Douglas Southall. R.E. Lee. Abr. by Richard Harwell. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1961.

Nolan, Alan T. Lee Considered: General Robert E. Lee and Civil War History. Chapel Hill, NC: U of NC Press, 1991.

“Robert E. Lee,” Historic World Leaders, available from Gale

Research (2005) [journal online];

http://galenet.galegroup.com/servlet/BioRC;

Document K1616000355; Farmington Hills, MI.: Thomson Gale.

“Robert E. Lee: 1807-1870,” Encyclopedias of the Confederacy,

4 vols. Simon & Schuster, 1993. Reproduced in Gale Research (2005) [database

online];

http://galenet.galegroup.com/servlet/HistRC;

Document BT2335100766; Farmington Hils, MI: Gale Group.

Works Citied

[1] Albert Marrin, Virginia’s General: Robert E. Lee and the Civil War (New York: Athenum, 1994), 193.

[2] Edward S. Joynes from University Monthly quoted in Robert E. Lee, Jr., Recollections and Letters of General Robert E. Lee (New York: Konecky & Konecky, 1992), 280-81.

[3] Marshall W. Fishwick, Lee: After the War (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1963), 136.

[4] Joynes, quoted in Marrin, 281.

[5] Joynes, quoted in Marrin, 301.

[6] Robert E. Lee, personal letter (3 Mar 1868), quoted in Fishwick, 137.

[7] Lee, quoted in Douglas Southall Freeman, Lee of Virginia (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1958), 219.

[8] Lee, quoted in Freeman (1958), 219.

[9] Robinson, quoted in Fishwick, 141.

[10] Lee, 295.

[11] Marrin, 194.

[12] Johnston, quoted in Lee, 315.

[13] Fishwick, 145.

[14] Douglas Southall Freeman, R.E. Lee. Abr. by Richard Harwell (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1961), 538.

[15] Lee, quoted in Michael Fellman, The Making of Robert E. Lee (New York: Random House, 2000), 250.

[16] Lee, quoted in Freeman (1961), 530.

[17] Fellman, 251.

[18] Lee, quoted in Freeman (1961), 587.

[19] Johnston, quoted in Lee, 315.

[20] Lee, quoted in Fellman, 253.

[21] Fellman, 260.

[22] Fellman, 262.

[23] Fellman, 262.

[24] Lee, quoted in Fellman, 251.

[25] Fellman, 252.

[26] Lee, quoted in Charles Bracelen Flood, Lee: The Last Years (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1981), 152.

by Joe Scotchie

The year 2007 promises to be like no other. For it represents the bicentennial of Robert E. Lee. I won’t bore you with tales of political correctness. We all know the days are evil. We are all subjects of an ideological regime: Not surprisingly, Lee, along with George Washington and Thomas Jefferson, is a main target of the evildoers. To others, Lee is not so malevolent. Rather, he remains a strange figure, a man out of place in American history. He is forever the Man in Gray, a figure who achieved glory in defeat, all in a nation defined by Progress Unlimited. Defeat, occupation, poverty – Americans would rather not think about it.

Lee is not forgotten – at least to those who look hard enough. There are Lee Counties in 10 Southern states. (The "Lee Counties" in both Georgia and Virginia are for his father, Henry "Light Horse Harry" Lee, the famed Revolutionary War cavalryman.) There are 80-plus schools – and not all of them in the South – that bear his name, not to mention those streets, boulevards, parkways, plus the numerous monuments in his likeness, especially Stone Mountain, the largest outdoor sculpture in the Western Hemisphere. A previous generation was nostalgic for life "befoah de wah." Me, I’ll take life before the Interstate, when the Old Lee Highway, the Jeff Davis Highway, and the Dixie Highway were the main byways running through the Southland. For the Old South, Lee was an icon on which folks could nurse their wounded pride. The South lost – but look at what men it produced. In that age, from 1876 to 1941, the first great bulk of Lee scholarship was being produced. Starting in modern times, around the 1930s, Lee became a puzzlement to some. Biographers, novelists, poets, and historians have all struggled to "get Lee right." Robert Penn Warren thought that Lee was too smooth, too refined a character to ever be a subject for fiction. Warren’s fellow Agrarian, Allen Tate, quit a planned biography of Lee in frustration: He thought Lee was too image conscious (to borrow a modern term) to gather much sympathy. For decades, restless historians have sought to upend Douglas Southall Freeman’s contention that unlocking Lee’s true nature – specifically his ceaseless devotion to Christian morality – involved no great mystery.

Is understanding Lee that hard? Lee was stoic like the Roman, but that was the way of the gentleman. Still, he was human, plenty human. Lee’s life was marked by great ambition, legendary victories, only to face enormous frustration and finally, defeat. He was, in his own words, a man "always wanting something."

Lee was reared in Alexandria, Virginia, at a time when the legacy of George Washington dominated the local culture. Lee’s father, now sent into exile for failing to meet his debts, was a friend and contemporary of Washington. Lee grew up idolizing Washington. As fate would have it, Washington’s adopted granddaughter also lived in Alexandria. The families were acquainted with each other. And you just knew that Lee would marry Mary Custis. One can imagine the young Lee laying eyes on Mary and resolving right there to marry her. You’d almost like to be a fly on the wall for that courtship.

In his youth, Lee also cared for his mother. He burned equally to redeem the family name. At West Point, Lee would become the only cadet to graduate without receiving a single demerit – an astounding achievement that stands to this day. After West Point, Lee began his life on the road. The coming decades would see Lee stationed at among other places, Savannah, St. Louis, Brooklyn, New York, and West Texas. Ambition followed by frustration. Lee disliked being away from his family, even though he had no real home. Arlington, the mansion where his children were reared, was in fact the home of his father-in-law, George Washington Parke Custis. In between West Point and Fort Sumter, there was the Mexican War, in which Lee served with great valor and vigor. His performance caught the eye of General Winfield Scott, who now declared Lee the finest soldier in the entire U.S. Army.

Lee, of course, opposed secession, even labeling it as a "rebellion." "The only song I long to hear is ‘Old Columbia,’" he exclaimed as the Deep South seceded. However, wearing the blue and invading Virginia was asking too much. You had to wonder what the boys in Washington were thinking. "Having plowed her fields, he had a new sense of oneness with her," wrote the perceptive Freeman of Lee’s special attachment to Old Dominion. In addition, Lee, during the war, became convinced of the South’s rightness in not just moral terms, but constitutional ones as well.

And so, came Lee’s greatest challenge, greatest glory, and greatest frustration. I am not a military historian. Lee excelled through those lighting quick offensive operations, the ones with Jeb Stuart conducting cavalry rides around the opposition, Stonewall Jackson striking the first blow, and James Longstreet’s forces delivering the decisive follow-ups. After Jackson fell at Chanceslorsville, Lee still took the offensive at Gettysburg. After that epic battle, Lee assumed a more defensive posture, one that kept Ulysses S. Grant’s mighty forces at bay all throughout 1864. I would only add that the Western theater was important, too. Jefferson Davis’s decision to relieve Joe Johnston in Atlanta with John Bell Hood was as significant as the loss of Jackson. Hood abandoned Johnston’s successful defense of Atlanta for an heroic, but ill-conceived assault on Nashville. The Army of Tennessee was lost at a time when Lee’s men were still in the field. Plus, there is the story of Nathan Bedford Forrest and all the missed opportunities.

So why Lee? There is that constant fascination with the underdog, with Lost Causes, with how the losing side manages to endure. There also was Lee’s conduct, both during and after the war. He did win great battles against enormous odds. Plus, Lee was magnanimous in victory. He did not gloat or brag when a major battle was won. He knew the odds his army struggled under and the cruel reality of war – thousands of young men robbed of life at an early age. He referred to Federal forces as "those people" and even at times, "our friends." Finally, in defeat, Lee was regal. At Appomattox, he dressed in his full general’s uniform while Grant showed up late, chomping on his ever-present cigar and wearing only a colonel’s outfit. One can only recall James R. Robertson’s unforgettable description of that scene: "[It] was one of those rare moments in history when the vanquished commanded more attention than the victor."

After the war, Lee’s demeanor changed little. There was anger in private, the conciliatory stand in public. "How that great heart suffered," his son Robert Junior also observed. There was more, however, to his postwar life than melancholy. At Sulphur Springs, Virginia, Lee confided to Fletcher I. Stockdale, a former governor from Texas, that if he had foreseen the ravages of Reconstruction, he would not have surrendered, but instead died with his men right there at Appomattox.

Indeed, at Washington College, where Lee served as president, he truly was a man without a country. The descendant of two signers of the Declaration of Independence, the son of a governor of Virginia, the husband of the adopted granddaughter of George Washington, Lee was now a mere spectator to the tyranny of Reconstruction and all the graft and corruption in Washington City. It couldn’t have been easy.

In all, I’d say such pro-Lee scribes as Dr. Freeman and the Rev. J. William Jones read the man correctly. Rev. Jones might not have been an academic, but he was an intimate of Lee during the Lexington years. Self-denial and duty were the cornerstones of Lee’s life. He loved the latter word, declaring it to be "the most sublimest word in the language. Always do your duty. Never do less."

"Teach him he must deny himself," the elderly Lee told the mother of a young child. Here again, is the code Lee strived to live by: Self-denial, the determination to live for others. That does lead to frustration. At Washington College, Lee posted only one rule: All students must behave as Christian gentlemen. Lee fell short, as do all who take up the cross. The effort, however, is important. In that sense, Lee is hardly a failure. His life remains a fascination to millions around the world. Two hundred years later, the controversies, the adulation, and the debates rage on. Every year, the books tumble out of the presses. General Lee lives.

Joe Scotchie [send him mail] is a regular contributor to various conservative publications and the author of several books, including Revolt From The Heartland: The Struggle for An Authentic Conservatism (Transaction) and Street Corner Conservative: Patrick J. Buchanan and His Times (Alexander Books).

Copyright © 2006 LewRockwell.com

Robert E. Lee’s moment of leadership

It was a beautiful Sunday morning in late June 1865 in Richmond, Va. St. Paul’s Episcopal Church was nearly full as many local residents sought solace for their troubles. The Civil War had been lost, many chairs were empty at family dining room tables, and the South was being occupied by blue-coated Federal troops. Adding insult to injury, to regain the rights of citizenship one needed to apply for parole, a process that required a person to take an oath that repudiated the Confederacy. Southerners found it a bitter pill to swallow; most remained defiant.

The congregation listened intently to the sermon given by the rector, Dr. Charles Minnigerode. They were unaware that on this warm June morning, something symbolic of the efforts at Reconstruction was about to happen. The service progressed to the point where Minnigerode offered communion to all who came forward.

Just at that moment, a tall, well-dressed African-American man rose and walked quickly up to the altar rail, knelt and awaited communion. Minnigerode stood frozen, unsure of what to do. No one in the congregation moved.

The treatment of African-Americans by white churches in the southern states during this time varied widely. In some, blacks were allowed their own separate service, while in others, they were refused admission entirely. Considering the restrictions, most kept to their own places of worship. St. Paul’s had a section of the upstairs gallery that was reserved for blacks. If they wished to receive communion, they could do so only after the last white parishioner had returned to his or her pew.

Before and during the war, a black person attempting to take communion alongside whites could expect trouble. Typically, the offender would have been hustled from the church, jailed for disturbing the peace, and — quite possibly — whipped for indiscretion. Now, with the city under martial law, the congregation remained in their pews and the minister stood dumbfounded. The congregants looked at each other and perhaps whispered that something had to be done. But by whom?

At that moment, an older man in a gray suit stood up in his pew. Many realized that what he wore was his former Confederate Army uniform, with all insignia removed per Federal military decree. This was Gen. Robert E. Lee, who at the end of the war had commanded all the armies of the Confederacy. Although he considered himself a failure for losing the war, he was universally respected and loved across the South. The congregation no doubt looked at him as just the person to “fix” this uncomfortable situation; Lee was used to people obeying his orders. Without a word he stepped out of his pew and walked toward the black man kneeling at the altar rail.

Following his surrender of the Confederate Army on April 9, 1865, Lee had returned to Richmond, where his family was staying in a rented house. Arlington, the large estate owned by the family, had been seized by the Federal government and turned into a cemetery (now Arlington National Cemetery). The Lees had some other farms, but they had not been worked for years and were sacked during the war. Lee had no job and little income. He had reason to fear arrest at any moment.

During his journey to Richmond, soldiers Lee had formerly commanded approached him and whispered that he needed only to give the word and the war would start anew. Their former general’s answer was always the same: The word would not be given; go home, regain your citizenship and become an asset to the country.

One day a former Confederate captain came to Lee and asked him what he should do. Lee gently urged him to take the oath and apply for a pardon. The captain’s father was Henry Wise, a former Virginia governor, Southern general and a firebrand of the Confederacy. When he told his father he had applied for a pardon, the senior Wise raged and declared that the boy had disgraced the family. But when the boy replied that General Lee had suggested it, the senior Wise calmed down and said: “Oh, that alters the case. Whatever General Lee says is all right, I don’t care what it is.”

So now the devout Robert E. Lee was looked to by his fellow congregants to set the example of how they should react to an African-American who believed he was the equal of a white person in the eyes of God. Robert E. Lee knew exactly what he had to do.

He walked with a purpose up to the communion rail; all eyes in the congregation watched to see what he would do next. Without a word, Lee knelt down not far from the black man, looked straight ahead and also awaited communion. Following the lead of the most beloved figure in the post-Civil War South, the proud people of Richmond quietly came to the rail and knelt on either side of the two men already there. Minnigerode immediately began giving communion to everyone at the rail.

Sources: “Lee: The Last Years” by Charles Flood “Duty Faithfully Performed” by John Taylor.

Copyright © 2007 The Reno Gazette-Journal

|

|

Rebels in Rome: |

|

| The Catholic Church and the Confederacy in Civil War America |

|

Philip Gerard Johnson |

| REMNANT GUEST COLUMNIST |

|

“There are few...who will not acknowledge that slavery

as an institution is a moral and political

evil.” ...Robert E. Lee