80 Acres of Hell – Camp Douglas

Many have heard of Andersonville and alleged allegations of mistreatment of Union POW's, but none come worst than that of Camp Douglas a prisoner-of-war camp in Chicago, Illinois during the War for Southern Independence, or known as the Civil War, that held over a conservative number of 18,000 Confederate POWs.

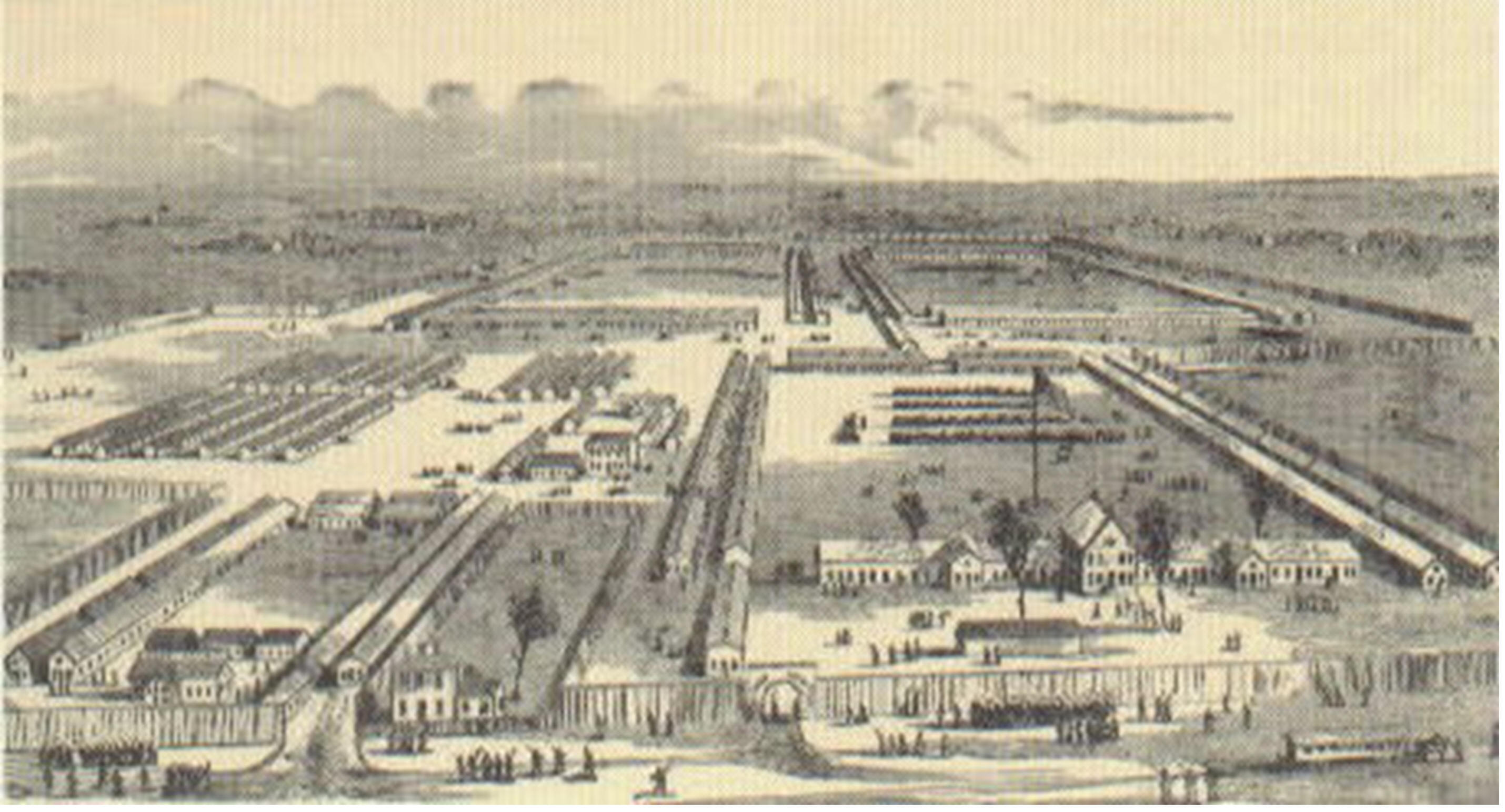

In 1861, a tract of land at 31st Street and Cottage Grove Avenue in Chicago was provided by the estate of Stephen A. Douglas for a Union Army training post. The first Confederate prisoners of war—more than 7,000 from the capture of Fort

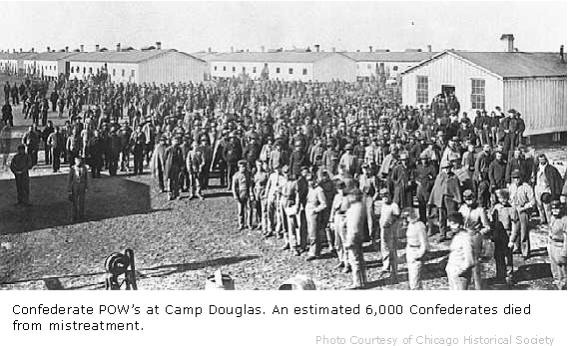

Donelson—arrived in February, 1862. Eventually, over 18,000 Confederate soldiers passed through the prison camp, which eventually came to be known as the North's "Andersonville" for its inhumanity.  It is estimated that from

1862–65, more than 6,000 Confederate prisoners died from disease, starvation, and the cold weather, although as many as 1,500 were reported as "unaccounted." The largest number of prisoners held at one time was 12,000 in December 1864. Accounts vary as to precise numbers. According to

"80 Acres of Hell," a television documentary produced by A&E and the History Channel, the reason for the uncertainty is that

many records were destroyed after the war. The documentary also alleges that, for a period of time, the camp contracted with an unscrupulous undertaker who sold some of the bodies of Confederate prisoners to medical schools and had the rest buried in shallow graves without any coffin. Some were even dumped in Lake

Michigan only to wash up on the shore. Many, however, were initially buried in unmarked pauper's graves in Chicago's City Cemetery (in today's Lincoln Park), but were re-interned after the war in 1867 at

Oak Woods Cemetery (5 miles south of Camp Douglas).

It is estimated that from

1862–65, more than 6,000 Confederate prisoners died from disease, starvation, and the cold weather, although as many as 1,500 were reported as "unaccounted." The largest number of prisoners held at one time was 12,000 in December 1864. Accounts vary as to precise numbers. According to

"80 Acres of Hell," a television documentary produced by A&E and the History Channel, the reason for the uncertainty is that

many records were destroyed after the war. The documentary also alleges that, for a period of time, the camp contracted with an unscrupulous undertaker who sold some of the bodies of Confederate prisoners to medical schools and had the rest buried in shallow graves without any coffin. Some were even dumped in Lake

Michigan only to wash up on the shore. Many, however, were initially buried in unmarked pauper's graves in Chicago's City Cemetery (in today's Lincoln Park), but were re-interned after the war in 1867 at

Oak Woods Cemetery (5 miles south of Camp Douglas).

Between 1862 and 1865, there were some half dozen commanders in charge of Camp Douglas. According to the A&E documentary mentioned in the above paragraph, two of these commanders were so inhumane that they made this camp worse than any other prisoner-of-war camp in the Civil War. The last commander of the camp, Col. (later Brigadier General) B.J. Sweet, denied any fruit or vegetables to the prisoners and has been blamed for the rampant spread of scurvy among prisoners during his tenure. Although some still maintain that Sweet re-acted to a genuine threat when he demanded and received permission to put the entire city of Chicago under martial law in 1864--allegedly because civilians were planning to free the camp's prisoners--others believe that this threat was bogus and that Sweet used it as a pretext to arrest individuals whose only crime was criticism of the camp's inhumane conditions. Several of these civilians, including the wife of a prominent Chicago attorney, were put in the camp with the prisoners of war. They were tried and convicted before a military tribunal in Cincinnati, Ohio. At least two of these civilians died in the camp. Another committed suicide while awaiting trial in Cincinnati. In 1866, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the trial had been unconstitutional.

The camp was called "80 Acres of Hell" by many of  the captured soldiers. Inmates were deprived of blankets, medical treatment, and food. To the immediate

south of the camp stood the University of Chicago, from which seminary students provided charitable aid to the prisoners when allowed to do so by the camp commanders. At one point, some prisoners ate a dog, and even rat meat came to be regarded as a delicacy. The president of the U.S. Sanitary Commission once

inspected the prison and gave a report of an "amount of standing water, of unpoliced grounds, of foul sinks, of general disorder, of soil reeking with miasmic accretions, of rotten bones and emptying of camp kettles.....enough to drive a sanitarian mad." The barracks were so horrendous, he said, that "nothing but

fire can cleanse them."

the captured soldiers. Inmates were deprived of blankets, medical treatment, and food. To the immediate

south of the camp stood the University of Chicago, from which seminary students provided charitable aid to the prisoners when allowed to do so by the camp commanders. At one point, some prisoners ate a dog, and even rat meat came to be regarded as a delicacy. The president of the U.S. Sanitary Commission once

inspected the prison and gave a report of an "amount of standing water, of unpoliced grounds, of foul sinks, of general disorder, of soil reeking with miasmic accretions, of rotten bones and emptying of camp kettles.....enough to drive a sanitarian mad." The barracks were so horrendous, he said, that "nothing but

fire can cleanse them."

Although, during the first year or so of the camp's existence a number of prisoners of war were allowed to buy their way out of the camp, this means of escape was eventually cut off. The only way out, aside from escape, was to pledge loyalty

to the United States and agree to fight for the Union. Many soldiers took this oath and were sent to fight Native Americans in the West. At the end of the war, only prisoners who agreed to take the oath were given train fare to the  South. Those who

still refused were forced to return home by their own means which often meant walking across several states.

South. Those who

still refused were forced to return home by their own means which often meant walking across several states.

A personal experience of being a POW at Camp Douglas is available at a webpage by Michael Gay, a descendent of Milton Asbury Ryan of the 14th Mississippi Infantry Regiment, Experience of a Confederate Solider in Camp and prison in the Civil War 1861-1865

After the war, the camp was discontinued and the infamous barracks and other buildings demolished. Today, modern condominiums fill most of the site.

Recommended Reading